One of the largest changes in the latest CBA — perhaps the largest — was the introduction of the MLB Draft Lottery. Instead of the draft order being dictated as the inverse of team records (from worst to best) as it was for decades, it is now determined by chance. Teams are given a percentage chance for the number one pick each season based on their record. The draft order is then determined by a random selection of magical ping-pong balls.

The draft lottery was seen by many as a solution to combat tanking. The process relied on the idea that teams would spend more often if they couldn’t tank for a guaranteed top draft pick. The tanking strategy has become a focal point among fans and the media over the last few years. Instead of letting the team lose in hopes of future success, why not just invest in your team’s roster year in and year out?

There — in the same avenue that it hoped to improve — lies the issue with the Major League Draft Lottery. Now two seasons into the Lottery’s existence some unintended consequences are starting to make themselves apparent.

The Draft Lottery and the coming scapegoating

The MLB Draft lottery isn’t going to motivate teams to invest more in their team’s success. It won’t motivate frugal (dare I say, “cheap”) owners to spend any more than they already have. If an owner was already unwilling to spend on the success of their organization, what difference would a handful of draft slots make? Yet, here we are. The Royals, owners of a miserable 121-203 (.373) record over the last two seasons, will pick sixth next summer.

Last season, the team held the fifth-highest odds of receiving the top pick in the draft. They had the fifth-worst record in baseball in 2022 but would go on to draft eighth overall. The team hasn’t had a top-five pick now in what will be four consecutive drafts. Yet, despite the recent trend, the team has spent sparingly. To be fair, there is still a ton of time for them to spend on their 2024 roster.

The team was linked to free agent Lucas Giolito on Tuesday. What happens if the team doesn’t spend up to improve their franchise-worst 2023 win total? Will the ownership and front office then blame themselves for poor scouting and drafting? Will they own the blame for a lack of spending? No, instead the team will blame their poor luck in the draft lottery, citing lost draft pool capital among other things. They already started to do so after Tuesday’s lottery.

“The slots are one thing…but there are also the finances attached to it.” While General Manager J.J. Picollo isn’t wrong in the slightest, he’s alluded to the real issue plaguing the team now for many years. The team will have a smaller draft pool to spend with the sixth overall pick than they would have had with a top-three selection.

The more important concern should be around selecting the best talent for the future of the organization. I’m a strong believer in Frank Mozzicato and his future prospects. However, how much better shape would the farm system be in if the team had selected higher-ranked talent such as Harry Ford or Andrew Painter? Again, in 2023, the team opted for draft savings instead of taking the better-ranked talent. The book will be out on Blake Mitchell for a long, long time. It could even come back as the right pick in the end. But how good would the farm system look with someone such as Kyle Teel, or the five other current Top 100 prospects taken after Mitchell?

The draft pool capital matters substantially for the Royals. That doesn’t change the fact that it signifies a much larger issue plaguing Major League Baseball that is still yet to be addressed in any meaningful manner. The Royals are rarely worried about acquiring the best available talent without caveat. There’s always a “but” or a “considering” involved. The team rarely makes a move — in the Draft, through trades, or Free Agency — that doesn’t in some way become handicapped by cost. A large part of that is the fault of the Royals and their ownership’s willingness to spend. However, the larger blame still falls on the League itself.

Without a true financial overhaul, small markets will stay buried

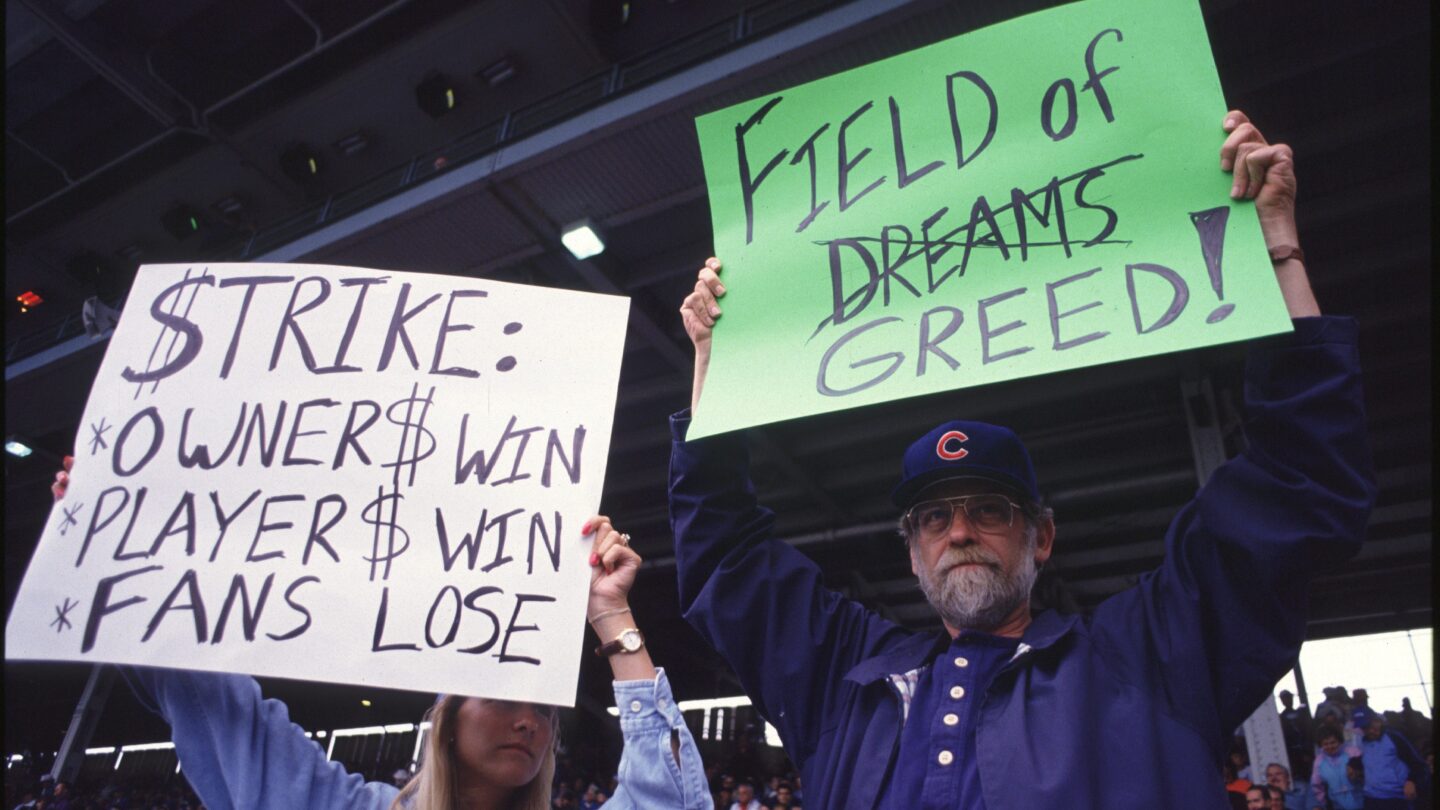

Back in 1994, the MLB and its players found themselves amid a work stoppage. It was the eighth and longest work stoppage in the history of the League. As a result, the remainder of the season after August 12th, including the postseason and World Series, would be canceled. It was the first time in any North American Professional Sport that a postseason had been canceled due to labor stoppage.

Craig Edwards dived into the history and how we got here in an excellent piece for FanGraphs back in 2020. In it, he outlined how the growth and change in television revenue vastly changed the league’s financial landscape.

At the time of that deal, teams like the Brewers and Indians were making around $3 million for their local broadcast rights; league-wide estimates pegged the average as between $4 million to $5 million per year. Factoring in the first national deal with ESPN for $100 million per year, teams made roughly $14 million per year off of those contracts. Local TV deals accounted for roughly 10% of MLB revenue, while national contracts with CBS and ESPN amounted to roughly one-third of total MLB revenue, with the latter effectively providing the sport with de facto revenue sharing. Today, the local and national television numbers are pretty close to equal at about 15% of MLB revenue each.

Payrolls around the league jumped huge amounts in 1991 after an agreement with CBS on a large TV contract. Then, CBS lost a ton of money on that contract agreement with the MLB. Other networks had already lost their share of money in similar scenarios, meaning that the league was left with a looming loss of revenue. As a result, payroll around the league shrunk massively in 1993. The players didn’t like that, and the strike then happened a year later.

Owners around the league feared that small-market teams could be left in the dust without a mechanism in place to share those growing television revenues. According to a Washington Post look back in 1995, the Owners wanted to approve a revenue-sharing plan only with salary mechanisms in place.

“The owners already have approved a revenue-sharing plan that would transfer $58 million in subsidies annually from large- to small-market clubs. That plan, however, takes effect only in conjunction with a mechanism to curb players’ salaries — either a salary cap or a payroll taxation system.

With labor negotiations between the owners and players stalled, the owners aren’t close to getting such a mechanism in place. Small-market owners say they need revenue-sharing — with or without a new labor agreement — to survive, but large-market clubs apparently remain wary of providing such subsidies without a salary cap or payroll tax.”

The league and its owners wanted a salary cap back in 1994. The large markets were wary of sharing their large television revenue if it didn’t mean they could be guaranteed a limitation on player salaries. The New York Times outlined a proposal from owners in June 1994. The proposal included a “more evenly based payroll structure.” It also opted to eliminate salary arbitration and grant players free agency after four seasons of service time instead of six. The salary cap and that proposal were never voted in and the effects of the developing financial landscape are still clear today.

In 1990, the Kansas City Royals had the largest payroll in all of Major League Baseball, at just over $23 million. By 1995, the difference was stark. The Royals payroll that season was a tad north of $31 million. That mark ranked 18th in baseball, and far behind the Yankees at $58.1 million. By 2000, the gap between the Royals’ payroll ($23.4 million) and the Yankees ($92 million) was even steeper. That gap has continued to grow exponentially ever since.

By 2010 the gap between the league-leading Yankees and the Royals (20th-highest payroll) was up to $134 million. In 2011, Alex Rodriguez made $31 million by himself — just $5 million less than the Royals entire payroll. The 2023 Yankees fielded a total payroll of $334.2 million. That mark is now more than $258 million more than the small-market Kansas City Royals. The strike of 1994 was just a sign of things to come. No matter how you feel about owner spending, small market teams have been left in the dust.

Sure, the Royals could spend more. It’s probably safe to say they should. Whatever you believe, it doesn’t change the fact that $30 million for the Royals is vastly different than $30 million for the Yankees. The League has left small-market teams behind and done nothing to even the financial playing field. The latest attempt — instituting a Draft Lottery — is nothing more than putting the cart before the horse. If the league wants teams to compete and wants them to prevent tanking, there’s nothing more impactful to that cause than evening the playing field on the open market.

If small-market teams could spend alongside the Yankees, Dodgers, and Mets then tanking would fix itself through the fair market. The Dallas Cowboys almost certainly bring in substantially more revenue than a team like the Titans but the payroll limitations are the same for each. A salary cap is the only true solution to motivating teams like the Royals and Pirates to invest in their roster. Until then, the teams are simply doing what they find feasible. Why should they spend and sacrifice more financially just to put themselves on an even playing field?

The newest CBA billed the Draft Lottery as a solution. In reality, it’s become the newest problem and should’ve always been seen simply as a helpful additive. The Royals have now gotten the short stick in the lottery two years in a row. That doesn’t hold a candle to the short stick they’ve been dealt for the better part of three decades. The draft lottery is a terrible system in a league without any true financial equality and teams like the Royals are the only ones who will feel that loss.

Discover more from Farm to Fountains

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.